One thing that any transitioning violinist must realize when playing the viola is that nearly all bow arm techniques require a greater amount of physical mass to produce the same articulation or tone. Primrose once said that young beginners who start on the viola (who have had no previous musical training) develop a less clear sense of rhythm because the instrument literally requires more time and preparation to make a prompt sound. While some violinists may view this as a defense mechanism (if this includes YOU, I permit you to leave this blog while you are at it...), there is an undeniable truth that viola playing requires more weight and tug in the string for tone production than violin playing does. Think about how often conductors tell low brass players to breathe in advance so that their entrances are in time with the rest of the orchestra...same deal with violas. UH OH - did I just compare my own blessed instrument to the tuba???

The bow hold is an essential aspect of the bow arm, and below I will describe the basic differences between the three major versions.

The Franco-Belgian (or French) bow hold keeps balance in the middle of the hand (second and third finger) with a bent thumb, and curved pinky, providing flexibility in the hand yet set up in a way that the hand doesn't exert dominance in actually moving the bow. In other words, the arm takes control of the stroke more than the hand does. The shoulder must be released, and the elbow must be low so that the arm works with the natural force of gravity. Some players of the Franco-Belgian grip include Sarah Chang (beside), Karen Tuttle, and Kim Kashkashian.

The German bow hold is a widespread bow grip with pretty equal spacing between each finger. The fingers make contact with the stick at the joint closest to the fingernail (sometimes even the pinky touches the bow there rather than curving over the top of the stick), and the thumb is relatively flat.

Above is Scott Slapin (the first violist to record the Bach violin partitas and sonatas!), whose grip is reminiscent of the German grip (disregard the raised shoulder in this photo - that is BAD NEWS for violists!). In some ways, this grip rarely exists today in its true form, but modern interpretations of the Baroque grip are quite similar to the German bow hold. Check out this link of Tafelmusik to sooth your ears and see a Baroque bow hold in action!

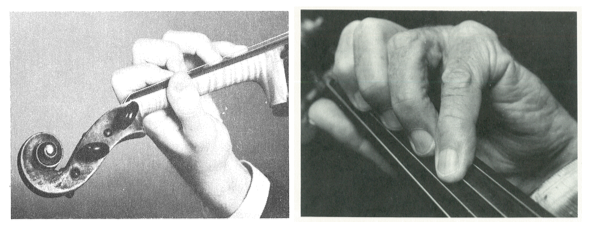

Lastly, there is the Russian bow hold, championed by players such as Heifetz (pictured above), Primrose, Auer, and Flesch. This grip features hyperextended fingers that naturally implement pressure to the string. Although the fingers are already at extension, they still maintain their flexibility. Often times, the arm and elbow are quite raised to prevent a bend in the wrist that pulls weight from the string. The Russian school of violin playing veers quite considerably from European traditions, which can explain some of the "genealogical" trends found in my earlier post: What these pedagogues mean to us now....

In violin playing, any of these grips could be effective because the amount of natural weight from gravity needed in the string for a clear sound is easily achieved given the dead weight of the bow and hand. However, in viola playing, the Franco-Belgian grip is quite dominant because as it forces the arm to take control of the stroke rather than the hand (as described above), natural arm weight enters the string to produce that same clear sound. Interestingly, Primrose, who played viola with a Russian grip (which generally presses extra weight into the string with the hand) said a good sound could never come from the viola if it came from added (hand) pressure, but he was an sort of exception to his own rule. Notice in the video below of him playing some Bach (and here of Milstein playing Bach on the violin in a similar technique) that he must play close to the tip in order to create a counterbalance for all the added pressure put into the string from his hand.

Bow hold exceptions aside, the primary right hand consideration (or arm consideration in these next paragraphs!) between violin and viola playing is the positioning of the elbow. Viola playing greatly favors the use of the Galamian arm plane, which includes a plane from shoulder to elbow (an un-raised shoulder, to be exact!) and from elbow to wrist. In fact, Galamian's technique all around leans away from the Russian school, thus it is more Franco-Belgian. Watch Perlman and Zukerman play the Handel-Halvorsen Passacaglia to get a perfect view of this setup (below). Both were violin students of Galamian, but in this video you can see Zukerman making a convincing switch to the viola that is facilitated by the lineage of his technique. What is even cooler is that you can see Galamian's teaching on both instruments simultaneously!

In the long and the short, right hand technique is incredibly divergent by school of discipline, but physically speaking, the Franco-Belgian/Galamian offshoot seems to be the most effective, and in today's playing, is more common at least in the viola world.

HOPE THIS HELPS!!

ll3